POST-SOVIET RADICALIZATION

An event that symbolically marked the failure of the modern project was the fall of the Soviet Union. Although controversial and multi-faceted, that event marked the ideological failure of soviet socialism, giving rise to conditions named as well as Post-Soviet.

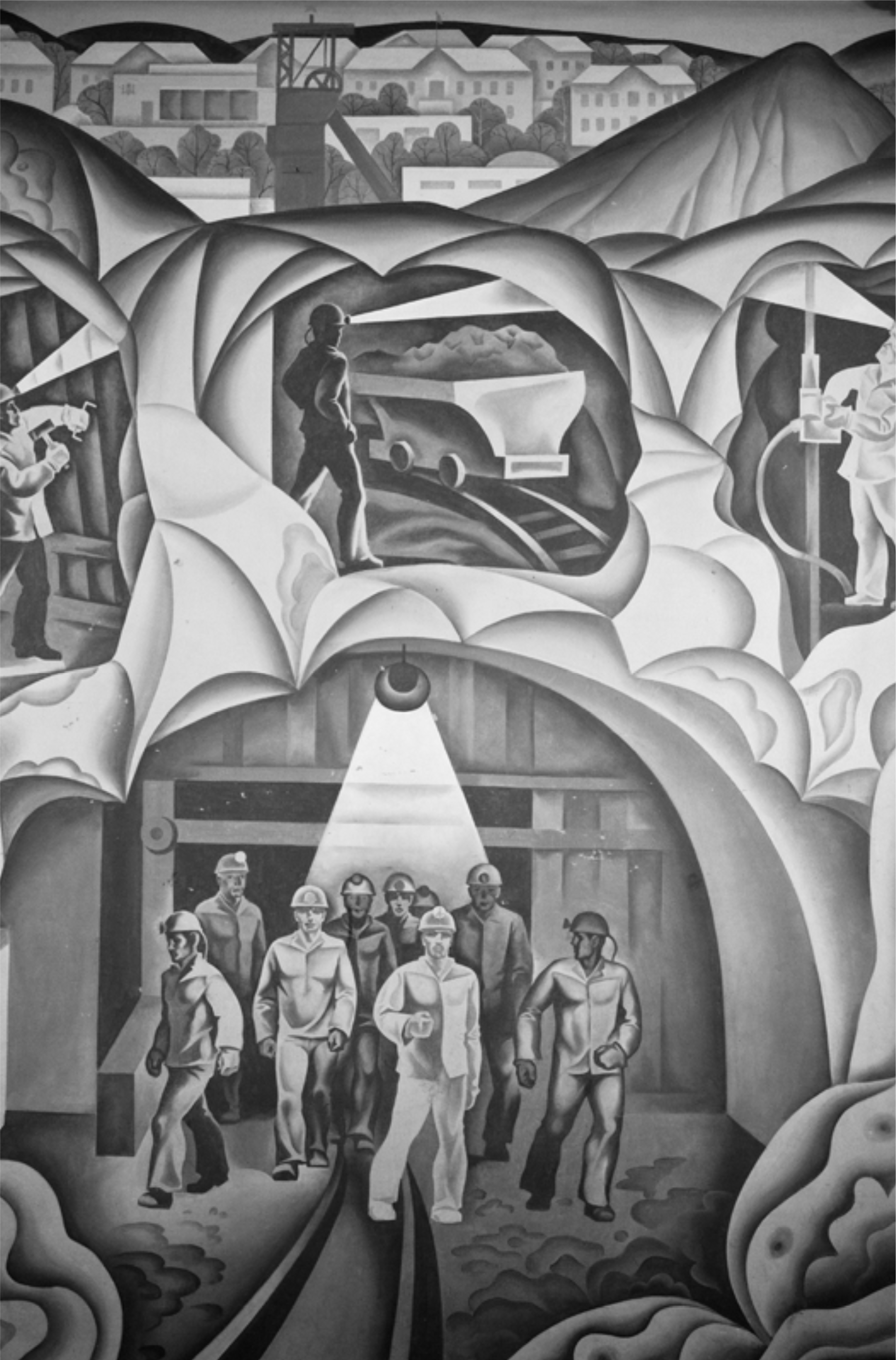

Source: Fyodor Telkov, 36 views, http://fyodortelkov.ru/projects/36-views/

Copyright © 2022 Fyodor Telkov

For this event, to account for the failure of the whole modernist project, it must be acknowledged that Marx’s modernity consisted of his belief in a rational dimension of men. Eventually, with science and technology, objectivity, ‘and calculus’ one could even predict when and why capitalism would have failed which is Marx’s historical materialism or an objectivization of history. In addition to that, we must remind that ‘Soviet-type planning, is the apogee of Fordism, Lenin embraced Taylor and the stopwatch. Soviet industrialization was centered on the construction of giant industrial plants, the majority of them based on western mass-production technology’. [17] For many, the promise in the liberatory dimension of socialist life was the most truthful accomplishment of a rational and rationalizing ideology. Krishan Kumar states that ‘The end of the century, the end of communism, and the end – say – of modernity, seem to possess at least an “elective affinity” for one another’. [18] In this respect, Soviet ideology made the routinization of novelty and a progressive idea of the future the main agent of its propaganda. It fabricated the idea of a ‘new man, the Bolshevik specialist, engineer or functionary, [who] came to represent a new code of social ethics, which was sometimes simply called Kultura. In keeping with the cult of technology and science, Kultura emphasized punctuality, cleanness, and businesslike directness’. [19] In soviet and post-soviet society, we therefore, find a clear link between ideology, technique, history, and alternative social narratives. To the failure of the Soviet project, the world that came after, is ‘with no alternative’, and, as said before, once accomplished, this flattening is empty and meaningless. For these reasons, therefore, the Russian context becomes extremely relevant in terms of the relation between Soviet society and modernism and the emergence of a possible ‘ideology of failure’.

The same paradoxical nature that fueled the coming of western modern and communist ideas from Europe in what seemed to be a distant and non-suitable context for that culture and theories to land, is now radicalizing the crisis of its failure. When talking about the paradoxical inception of ideas from the west, Mikhail Epstein in ‘The Origins and Meaning of Russian Postmodernism’ points out that ‘the same paradox pertains to the problem of Russian postmodernism. As a phenomenon which seems to be purely Western, in the final analysis, exposes its lasting affinity with some principal aspects of Russian national traditions’. [20] The traditions that Epstein is referring to are the ones concerning a recurrent detachment in Russian culture between reality and a simulacrum of reality, which can be traced back to imperial times. The symbol of this idealization of reality is the city of St. Petersburg. A city ‘composed entirely of fabrications, designs, ravings, and visions’.[21] a city in which three revolutions could take place, in light of its nature as a stage for conceptualizations of realities to take place.

In this context, the externalization of reality into distant ‘object’ that occurs in the modern techno-scientific ideology, happens to match perfectly with the culture of a country that is ‘more susceptible to mistaking phantasms for real creatures’. [22] The production of simulacra of reality being the heart of a proto-post-modernity in Debord’s work when saying that ‘the whole life of societies in which modern production conditions prevail is an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly experienced has moved away into a representation’.[23] A world of externalized objects which are forced and fitted into reality, acting as its substitute.

Thanks to its preventive inclination towards objectivization, therefore, Russian culture embraced and superimposed modern culture onto its physical territory more radically than other countries, and now the signs of its collapse are even more evident.

To an even higher degree of radicalization, the more explicit spatial productions of this criticality are to be found in cities in which the only purpose was the development of the progressive culture of modernity like Degtjarsk. What is called in Russian: Sostgorod, cities born out of the utopia of industrialization.