CHIMOPAR, A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Following Romania’s independence in 1878, the government promoted the growth of the industrial sector. As a result of this shift towards industry as a more significant economic contributor, sites such as Chimopar began to emerge within the city. Chimopar was founded at the end of the nineteenth century and is one of the oldest chemical factories in Romania, its primary function being the production and supply of plant fertiliser for the country, and gunpowder for the Romanian Army. During the Communist Regime, the site was expanded to keep up with the growing demand in products, and employed over 900 workers. It is possible to imagine the site as a once bustling and hectic place, filled with an air of rigor, operation and production.

In 1923 and 1979, the site faced two major explosions. However, it was not until the disbandment of the Soviet Union at the end of the twentieth century that the factory truly began to fall into decline. With a massive decrease in demand for raw products, the site began to make significant efficiencies, limiting the number of workers to just over 60. The factory remained operational only on a small corner of the site, leaving the remainder to fall into disrepair and decay.[4] The disused site became an open invitation to new inhabitants and offered a playground of possibilities (fig. 8).

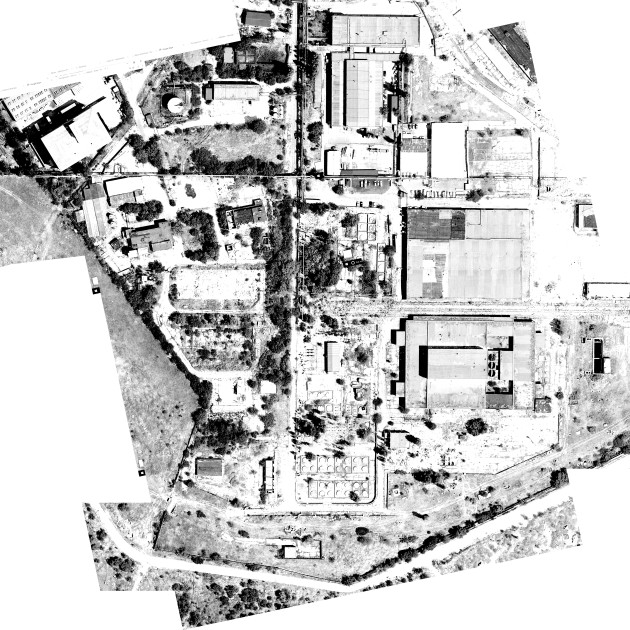

Figure 8. Google aerial map of Chimopar. The site is located in South-East Bucharest, at the periphery of the municipality border. The industrial zone spreads over several hectares and is sandwiched between the Dâmboviţa River to the south and Bulevardul Theodor Pallady to the north.

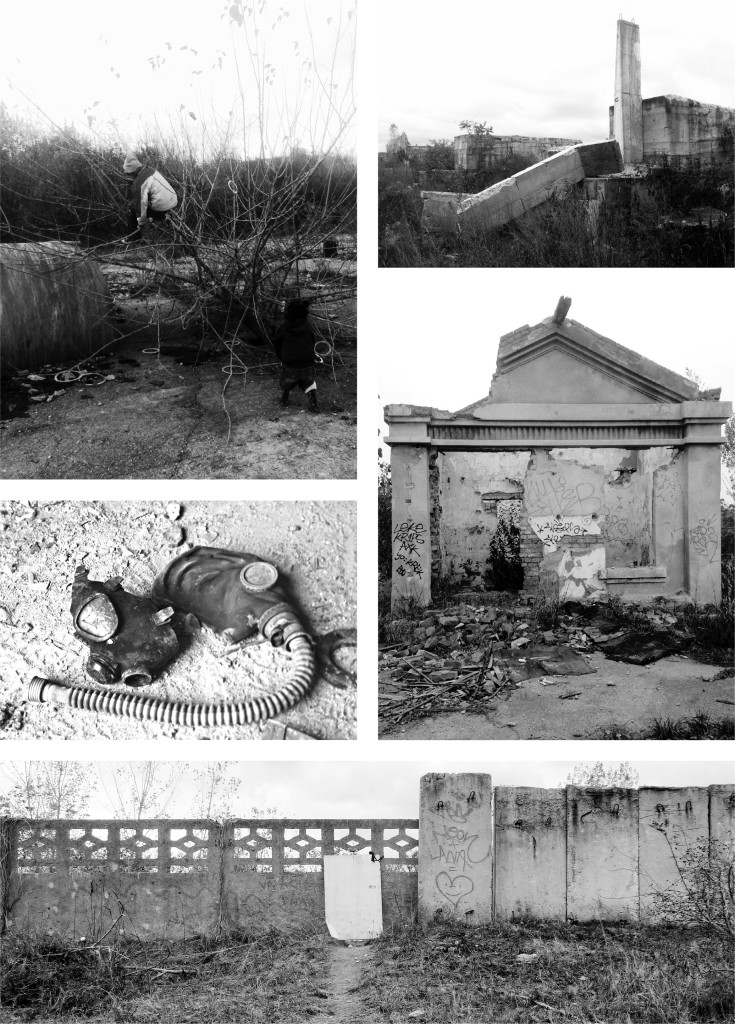

With no clear ownership, the buildings on the site have been left to deteriorate. Roofs, windows, and doors meticulously removed in a controlled manner by temporary occupants as they come and go from the site, leaving the bare carcass of a former machine. Whilst on first glance the site may appear empty, a closer observation of the site begins to reveal traces of its past and transgressive behaviours of its new inhabitants. Discarded gas masks speak of the history of the site, the workers, and protocols. Yet with the risk of the site’s previous operation, a boarded opening in the site’s boundary shows a clear act of defiance and disregard of danger. The act of creating a hole in the wall defines a point of entry. The door placed in front guards the entry and claims the passage between inside and outside, granting access to temporal visitors (fig. 9).

Figure 9a. Series of photographs taken at the Chimopar site that reveal traces of transgressive acts from the site’s inhabitants.

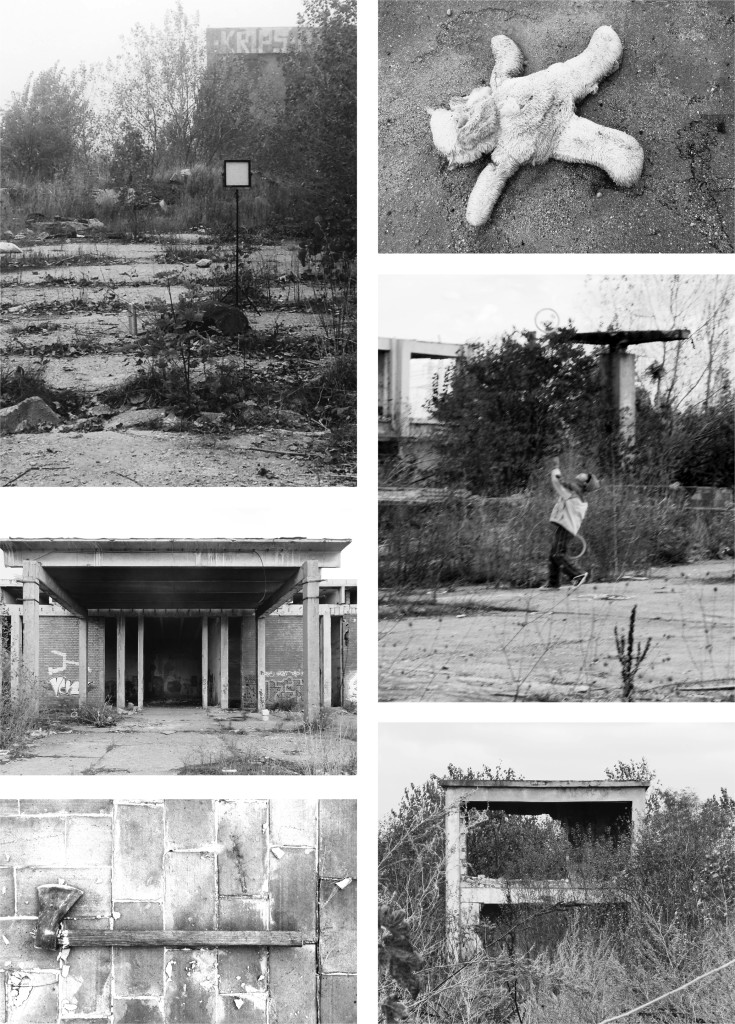

Film makers and photographers make use of the dramatic and emotive setting, whilst local artists come here to make their mark on the crumbling walls. The freedom and detachment from the city offers a wonderful opportunity for imagination, games and play. The temporal occupants of the ‘abandoned’ site begin to transgress and change the space, enriching the function, making it into a place where multiple functions co-exist.

The site offers a rich ground for observation of not only the existing structures and their spatial qualities, but also the constructed stories from traces of past inhabitants, however temporal. Their movements, actions and behaviours become part of the site and offer a re-reading of the site through their eyes. In order to develop an appreciation of the complexities of systems at work within this site it is first necessary to define the gazes or specific lenses through which the site is seen.

Figure 9b. Series of photographs taken at the Chimopar site that reveal traces of transgressive acts from the site’s inhabitants.