THE AGENCY OF URBAN DECAY

From a primary navigation through the city, the extent of decay becomes increasingly apparent as you move towards the peripheries of Bucharest. The notion of decay is particularly interesting in this city as it starkly contrasts Bucharest’s vast growth and urban development. The two concepts of decay and growth sit at polar opposite ends, both demanding a greater stake within the city. For this research, I have defined decay as a process that also brings forward particular spatial qualities. When describing Bucharest, it is clear the city is very much in decay, referring both to the process and spatial qualities within the city. There are many understandings of the term decay, but here I have chosen to highlight three in particular; decay as process, decay and nature, and decay and accumulation.

Figure 5. Wijnand Nuijen’s (1813-1839) depiction of River Landscape with Ruins.

Decay as process

Within the city, signs of decay become apparent through built structures. Buildings and man-made constructions, when left dis-owned, fall into decline as ruins. The textural qualities of the ruin and its determined resistance to the process of change seduces the eye and the observer. The Dutch painter Wijnand Nuijen’s (1813-1839) depiction of River Landscape with Ruins (fig. 5) frames the ruin as a distant, isolate object, yet embedded within its natural landscape. Studying the ruin itself, it is clear the structure has succumbed to various stages of decay; collapse of roof, removal of windows, deterioration of walls, overgrowth of nature. The building slowly becomes reduced to its bare structure, a skeleton of its previous life. Whilst the ruin seduces the observer through its qualitative properties of texture, light and space, it is also the quantitative understanding of the ruin that can offer alternative and defined insights into the process of decay. If, for example, the building in this painting was categorised by its stage of decay, the quantitative range would start with the building in its entirety as a completely man-made structure, and end with nature in its purest form. The painting freezes the building in this process of decomposition as it slowly becomes part of its environment once again.

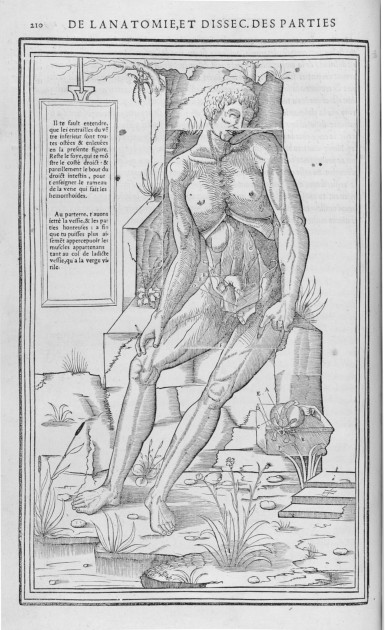

Figure 6. Charles Estienne’s illustration of dissected parts.

Decay and nature

As shown in the depiction of the ruin, decay is intrinsically linked with nature. The concept of nature and decay is related to the cyclical process of life and death, often represented by the body. Historically, anatomists have illustrated their understanding of the workings of the body in a bid to communicate their findings to medical professionals of their time. In the sixteenth century, French anatomist Charles Estienne made significant contributions by illustrating dissections of the human body (fig. 6). Whilst the focus of his illustrations was the dissection of body parts, his collection of work quite often made reference to both decay and nature. This strong connection between death and returning the body to nature emphasises the power and role of nature within decay. Unlike the quantitative stages of the ruin however, nature is expressed as a more organic form slowly taking over the body as it decays and decomposes. The illustration not only represents the body alongside nature, but also roots the body in the process of decay. As the body decomposes as a result of its ‘opening up’, it allows nature to enter in.

Figure 7. Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s etching of the ancient intersection of the Via Appia and Via Ardeatina.

Decay and accumulation

Like all objects, it is in the act of forgetting, mis-placing and neglecting which triggers the process of decay. Once forgotten, these objects slip from reality into memory. Memory is a place in which experiences, emotions, knowledge are stored; a physical construct within our minds. The Italian artist and archaeologist Giovanni Battista Piranesi played on this space of memory through detailed illustrations depicting his fantasies of these forgotten spaces. In his etching of the ancient intersection of the Via Appia and Via Ardeatina (fig. 7), the passage stretches out with an accumulation of ancient monuments, busts and references to buildings, constructing a visual map of his encounters and observations of Rome. It is only through Piranesi’s etchings that these forgotten relics are to a degree brought back into the present.