THE PLACE WHERE ONE IS BURIED

Jesse Verdoes

Mashhad, which translates as ’the place where one is buried’, was founded around the burial place of Imam Reza. What started as a simple grave in-between two villages, has over time developed into a massive pilgrim destination, materialized as a Holy Shrine. As the structure became the main focus point of the city, death is embedded in both its history and its architecture. Beyond its physical presence, however, the theme of death takes on a significant role in the consciousness of Mashhad’s residents. Due to its geographical location close to a fault line running across the Ashaf river, there is a constant looming risk of earthquakes and flooding in the city. Moreover, contemporary Iranian society is centered around death as a result of the political reformation after the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Following Ghorbani, this is reflected in the fact that ‘most religious centers, religious themes and forms, calendar plans and religious symbols are related to death’. [2] Adding to that given, Mirdamadi argues the existence of a death-conscious culture that emerged from the implications of the Iran-Iraq war, the prevalence of death in Iranian literature and the Shi’a teachings and rituals.[3] Particularly the religious rituals, like the mourning of Muharram, are extremely popular in Mashhad due to the presence of the Imam’s burial place

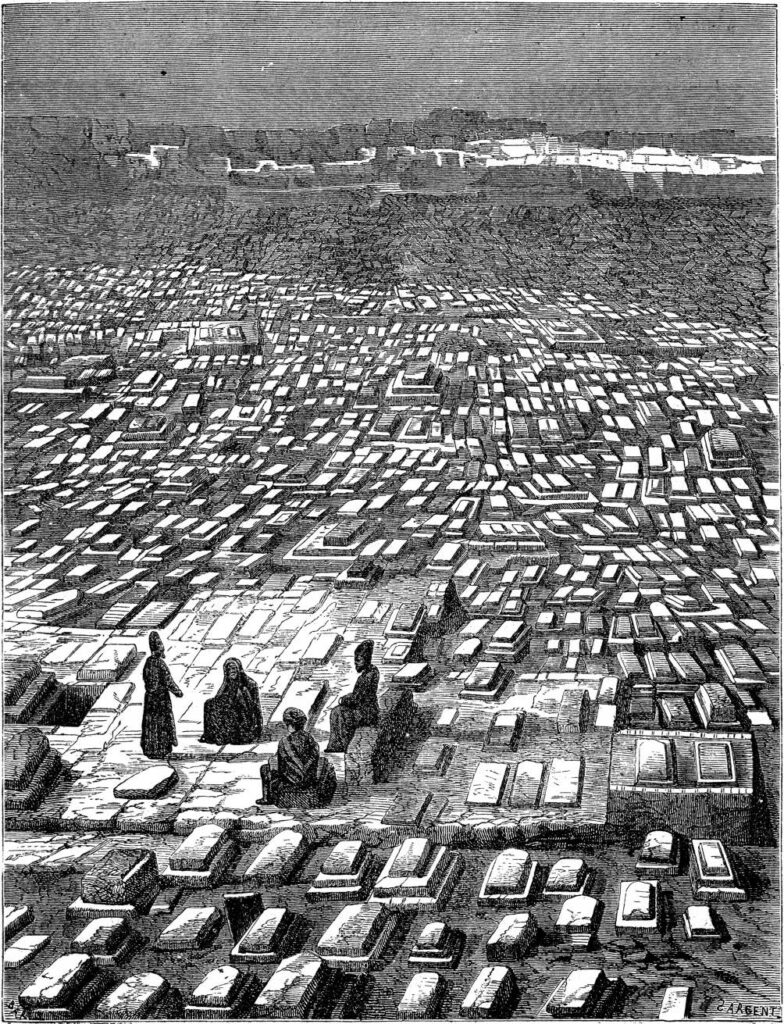

Source: De Bar, Old view of Katlgah cemetery in Mashhad, Iran. Etching. Alamy. 1861. https://www.alamy.com/old-view-of-katlgah-cemetery-in-mashhad-iran-created-by-de-bar-after-image150198098.html

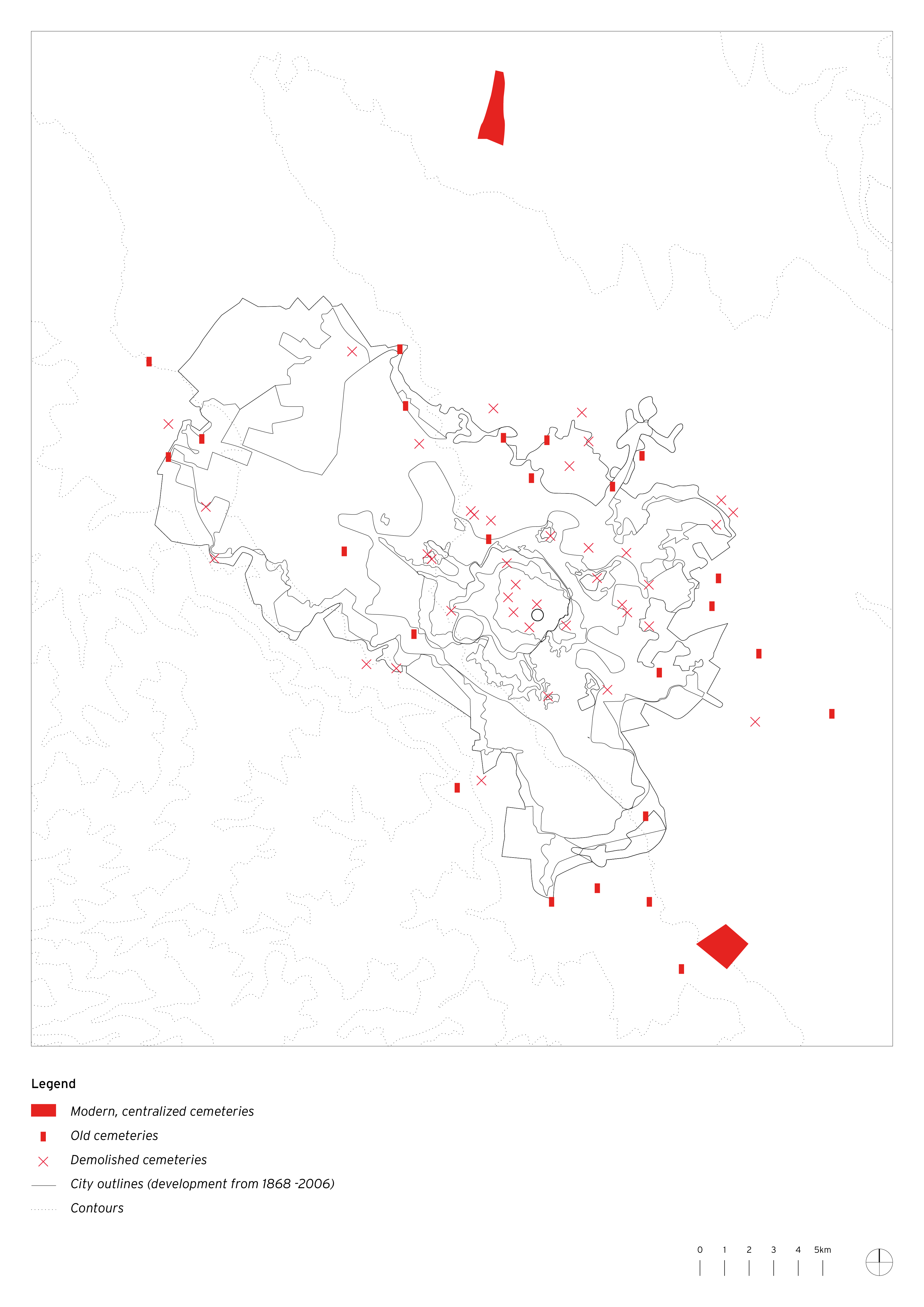

The importance of this grave in Shia culture made Mashhad a preferable place to be buried. This resulted not only in various tombs around the city, but also in the presence of grand graveyards around the shrine that largely exceeded the need of the population of the city itself.[4] These cemeteries were integrated in the organic morphology of the city and part of the daily life of its residents. The numerous villages around the city, which later became neighborhoods, each had their own cemetery where locals collectively carried out funeral rituals.

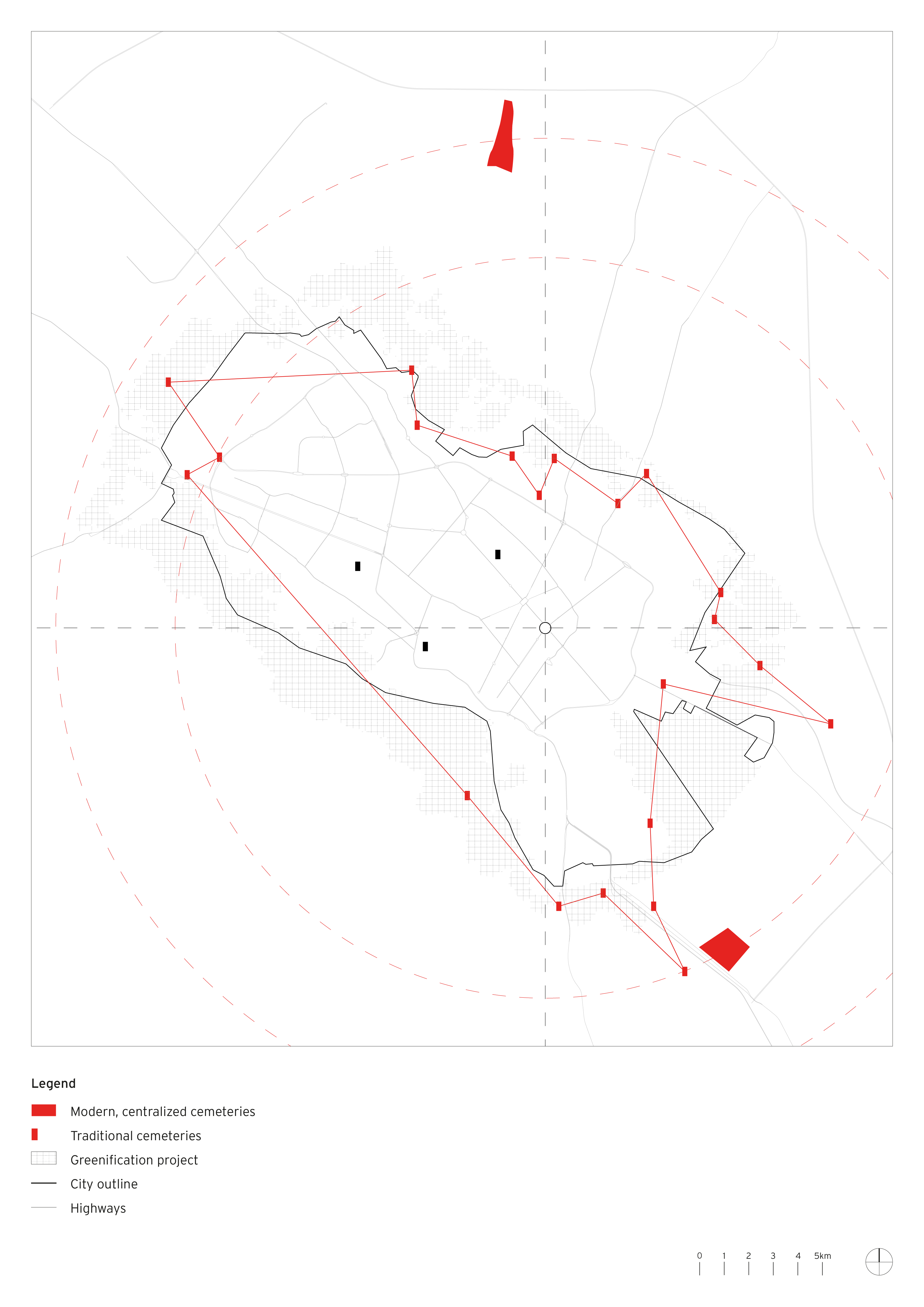

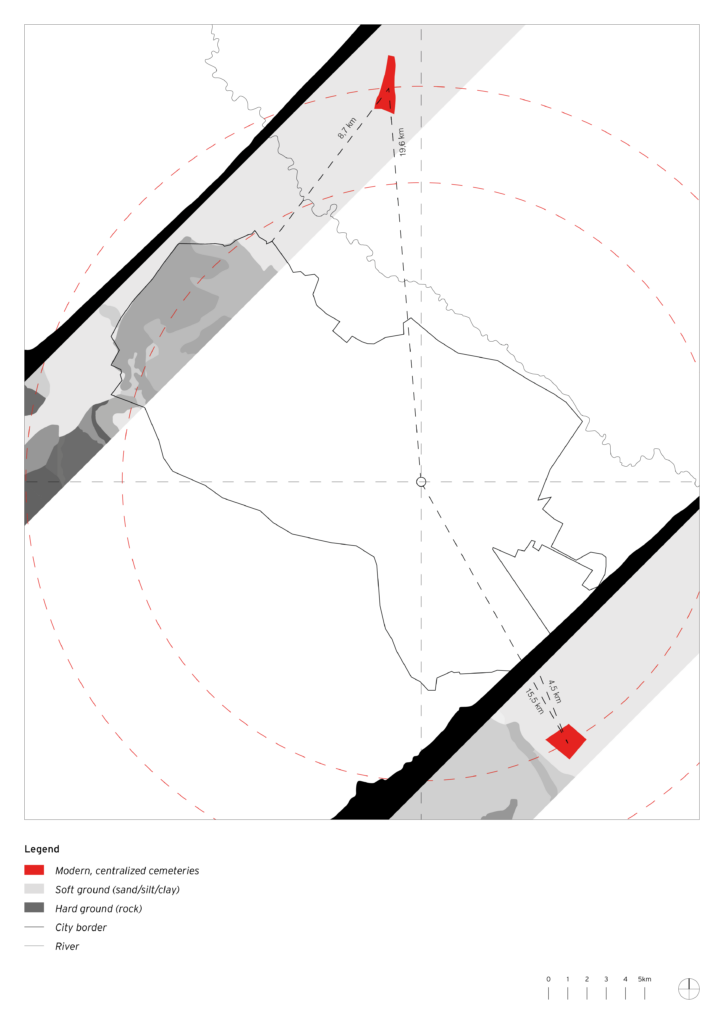

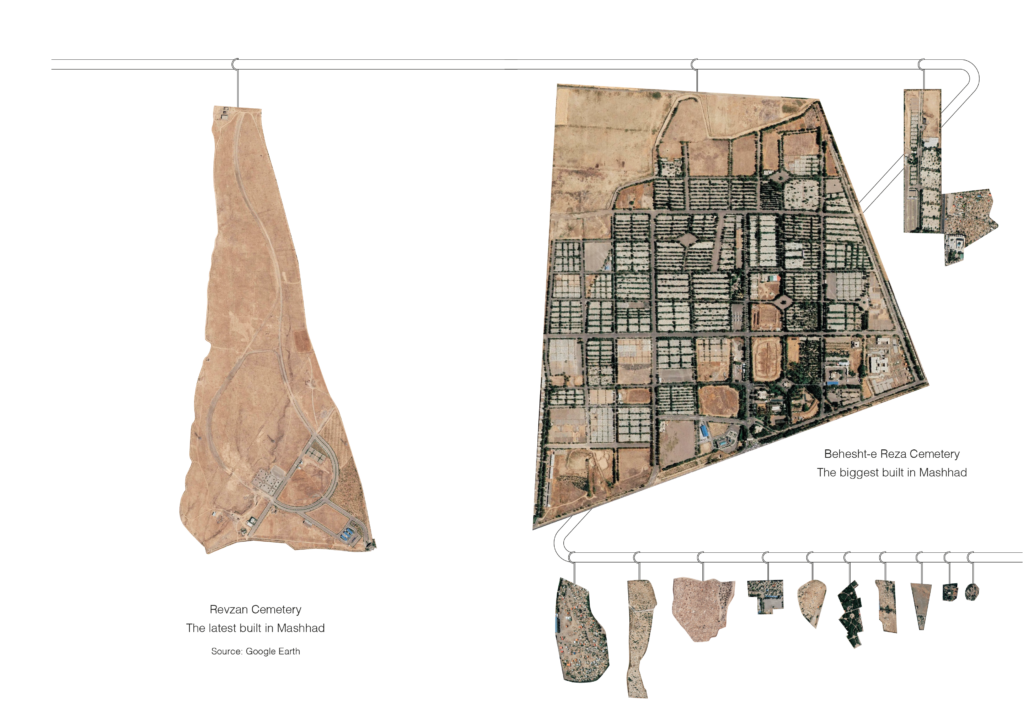

However, as the city modernized and the population increased rapidly, the city extended on the territory of the dead. Almost all of the former burial spaces that were situated around the shrine or belonged to the villages that became part of the city, are by now completely erased. One big centralized cemetery, named Behesht-e Reza, took over their role. As it is located just outside of the city due to the danger of water pollution, this modern burial place has become an isolated fragment situated next to one of the main highways leading out of the city. In this cemetery, set up almost like a city itself, the burial process is standardized and bodies are efficiently ‘deal with’. Compared to the traditional processes, the funeral ritual has become dehumanized, streamlined and bureaucratized. In the context of Iran, this is referred to as the sequestration death:[5] a trend which can be considered to be part of a world-wide problematic tendency of distanciation from death.[6]

While death plays a significant role in the culture and history of Mashhad, the relation between the dead and living has, by now, become increasingly severed. Due to the disappearance of burial grounds inside of the city and their displacement to the urban fringes, the formerly entangled territories of the dead and living are now completely separated. This contemporary situation results in a city that is burying its past and thereby taking distance from death. This project intends to research how architecture can deal with this changed relationship and how it could potentially be deployed to mediate renewed relations between life and death.