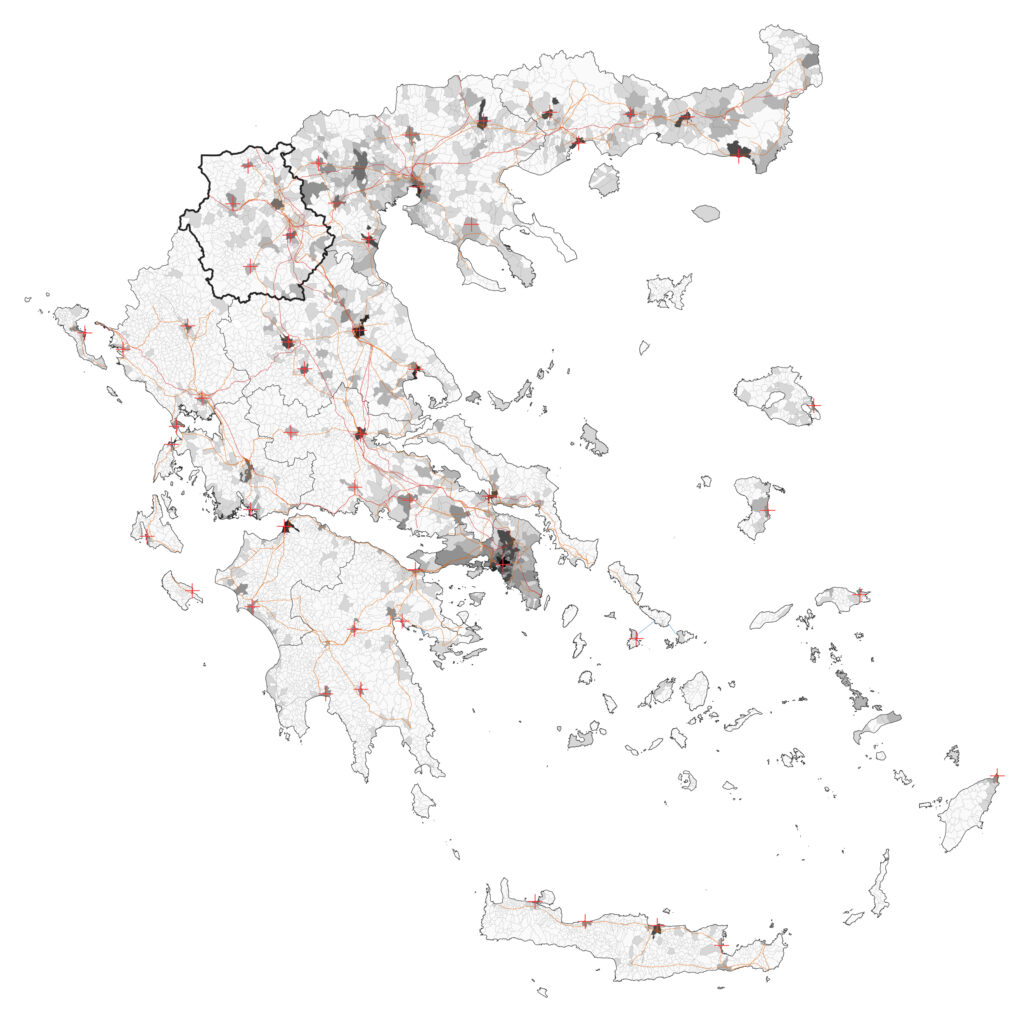

”CITY” AND ”NON-CITY”

As a result of decades of rapid development, infrastructure has created new systems, conquered new regions, and solved problems with solutions whose consequences are reasonably incomprehensible to us. Years of focusing primarily on ‘the city’ has subordinated the city’s surroundings to that ‘greater authority’. Yet in their very existence, urban areas were never self-contained nor self-sufficient. Their logic has always been supported and supplied by its surrounding areas. Urbanization processes were dependent on the production capacities of the hinterland, often limiting and predetermining its expansion.[1] The confined logistics of localized productivity allowed for a clear relation, as well as division, between cities and their hinterlands.[2] The process of industrial acceleration, along with the rapid development of infrastructure, diminished those rules and allowed for much greater distances between cities and their supply zones, while profit-oriented developments created new spatial as well as time scales which blurred the boundaries between urban territories. “What was created under the cloak of globalization, i.e., blurring the borders, strengthen the conquest of the market, and thus the conquest of the land.”[3] The logical division between the ‘city’ and ‘non-city’, or ‘urban’ and ‘non-urban’, has thus become ever more obsolete.

Cities and non-cities are not separate domains but are closely intertwined and mutually dependent.[4] Operational zones of the hinterland have often been absorbed as a result of the process of urbanization, even though allocated regions remain irretrievably exploited as monothematic supply hubs. Such strong, highly dependent relations are difficult to amortize. In consequence, when infrastructure becomes obsolete, little to no societal opportunities remain for the people, additionally contributing to negative social impacts and huge ecological costs. While planetary hinterland covers nearly 70 per cent of all urban land, there is no clear approach to studying and understanding it.[5] This raises the question to what extent these territories of hinterlands will be exploited and what will be their role after they have become obsolete? By closely examining the case of Western Macedonia, this work aims to investigate such relationships and their potential future. The region has already become a monofunctional, ecologically devastated landscape. Constantly being hollowed out socially, culturally and geologically,[6] Western Macedonia must undergo another transformation, bringing forward the question of the future shape and role of the hinterland, the context and conditions towards which this project intends to examine.