MODUS OPERANDI

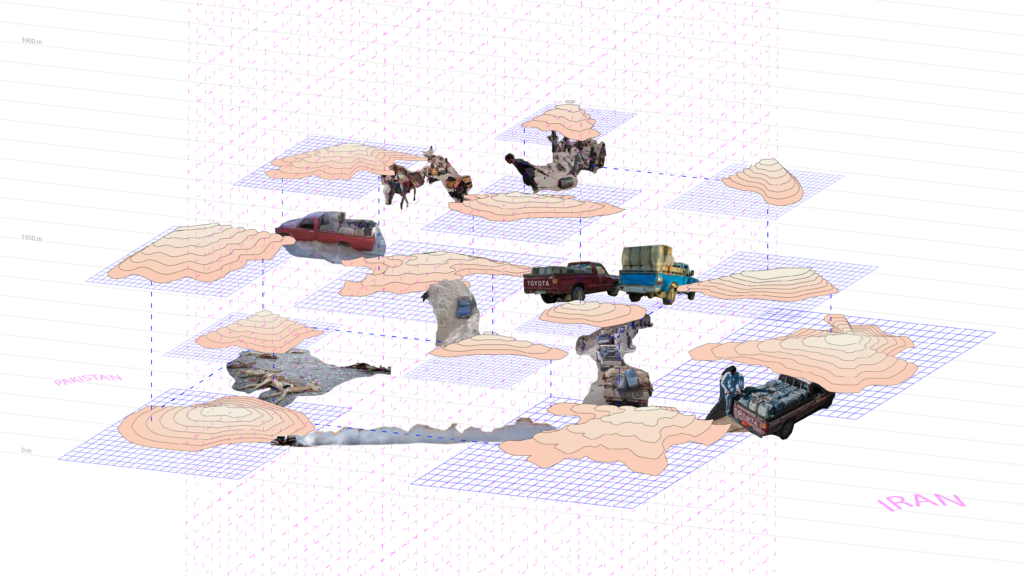

The Balochi oil smugglers’ characteristic modus operandi is very much apparent when looking closer at the area called Jodar, situated at the mountainous peripheric area of the Hamun-e-Mashkel desert. Jodar is the border destination of the biggest oil mafias – here, their commodity is traded in the informal marketplace. However, the smuggling route consists of several phases and starts well before reaching that point. It begins far away from the border on the Pakistani side, where the smugglers receive remote orders from their bosses to pick up the oil at the border. Once ready, they form a group of dozen or more pickup trucks, packed with various commodities to the very limit of their capacities. Their convoys can be easily recognized as most of them use characteristic Iranian-made blue pickup cars called Zamyads. They reach the area of the informal marketplace after several hours of driving through the desert. Once they arrived, they joined the line of other pickup groups waiting to enter the Jodar. On the other side of the border, smugglers tank hundreds of barrels and endeavor a risky journey through the mountains. The paths at the mountains are mined by the state forces. Therefore, the smugglers use donkeys to carry their barrels for them – the animals are led first in order to test the route for mines. Eventually, smugglers from both sides meet at the provisional marketplace at Jodar. The access to the marketplace is controlled and trade is informally regulated by Pakistani Frontier Corps, who collaborate with smugglers in exchange for bribes.

Regarding the smugglers’ modus operandi, one can distill a whole inventory of attributes, inherent characteristics, circumstances, and artifacts summing up the entire phenomenon. The nature of the living infrastructure of Balochistan can be described through the philosophical notion of Deleuze and Guattari’s assemblage. As Thomas Nail explains, assemblages, rather than being united bodies, are ‘more like machines, defined solely by their external relations of composition, mixture, and aggregation. In other words, an assemblage is a multiplicity, neither a part nor a whole’. The smuggling route consists of multiple independent nodes constantly (re)drawing special connections within consecutive steps. [12]

In the theory of assemblage, the division between social and the material becomes blurred. Agents of different natures (things, humans, animals) come together to create a temporal hybrid multiplicity before splitting and turning into operating as other functions in different places or times – independently or paired with another actor(s). As Deleuze and Guattari describe, [Assemblages] have elements (or multiplicities) of several kinds: human, social, and technical machines, organized molar machines, and molecular machines with their particles. [13]

Within the assemblage, the relationship between different components is fluid and prone to change and evolution. When regarding the smuggler’s modus operandi, one can perceive a parallel in the nature of this process – mainly in its constant dynamism and exchangeability of actors. Smugglers remotely place their orders, while others form groups, transmuting from individual particles to solid living infrastructure that executes these orders. Forming uniform groups, they are visually recognizable as they drive the same pickup cars. The role of the actors is also prone to be exchanged between them. In the smugglers’ hierarchy, due to the temporal circumstances, buyers may turn into sellers and employees may transmute to employers. A substantial part of the smugglers’ community are young children, being forced to act as if they were adults. On the operational side, the breeding cattle become a carrier, while in another circumstance, it is used as an indicating device. The very essence of the whole process – the act of trading – operates under the ambiguous position of law enforcement forces towards smugglers. Despite the official penalization of smuggling, different law enforcement groups participate in this process, taking various roles. Some of them become facilitators, others supervise the order of the trades, intermediate between smugglers or even compete with them. The state representatives, depending on the circumstances or the narrative, pose either as smuggler’s predators or allies, performing either as prosecutors or participants. Each of these actors, apart from having their inherent independent qualities, adjusts its role according to particular circumstances. Altogether, these interchangeable elements forms the tissue of a greater ‘living machine’ capable of adapting to the constantly fluid circumstances, creating cross-border fluxes.